Why I Kinda Give A F*ck About the Academy Awards

Some Musings on this Year's Oscar Nominations and Omissions

Today the 97th Academy Awards will be held at the Dolby Theater in Hollywood. Usually I’m indifferent to these awards and, in terms of my personal relationship to cinema, that hasn’t changed. But in an age of hyper symbolic politics, the conservative capture of major arts institutions, and increasing state-enforced censorship, it's hard not to feel like the stakes of artistic representation are as great as ever and that institutions like the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences have a role to play in combatting such forces.

Still, I die a little bit inside every time I see a celebrity profile about an actor’s transformation for a role on the New York Times home page, especially when adjacent to headlines about real global crises. It’s hard not to see this phenomenon as symptomatic of a culture that regards the most vital and most inane aspects of organized human life with equal frivolity. On the other hand, Tilda Swinton did offer some insightful remarks in one of those very profiles when asked about art’s relationship to politics:

The real question is: Who are we and how must we live? I don’t necessarily want to designate one thing as political activism and another as artistic practice and another as living your life. For me, there aren’t walls between any of them.

One must be careful not to mistake criticism of the Academy Awards, or the existence of the nominees themselves, for anything like the kind of direct political action that protects great works of art from the philistines who hate them for lacking some obvious instrumental value. And yet who gets recognized by this flawed voting body still matters, just as it matters what the Times puts on its front page. Both institutions play an enormous agenda setting role. They tell people what is worth their time and attention, and therefore deserve whatever criticism comes their way when they do or don’t esteem truly vital work.

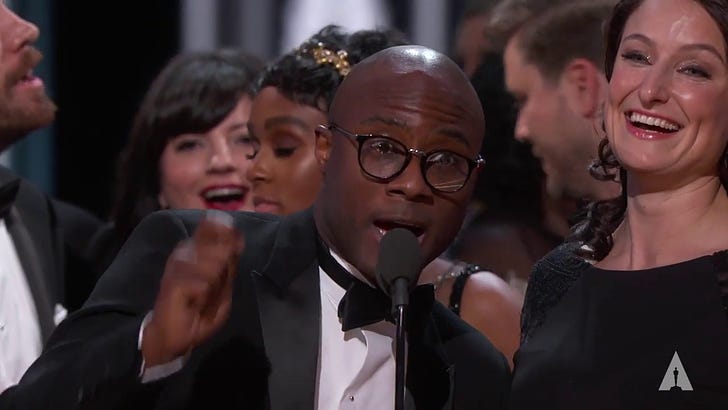

Speaking of recognizing vital work, I’m approaching this year’s ceremony with the 2017 awards in mind. You know: the year in which, following a disastrous envelope mix-up, Moonlight (2016) won Best Picture over rival favorite La La Land (2016).

Moonlight’s victory came as a surprise to many for several reasons:

La La Land had already cleaned-up at all the other awards shows and was therefore favored to win in terms of sheer momentum.

The Academy’s voting body is not known for its exceptional taste. It has a habit of awarding relatively mediocre fare, which is perhaps why there is often more talk of undeserved wins than deserved ones.1

The Academy favors movies about movie-making. There is a kind of self-aggrandizing at play, in which movies about movie-making, especially those about Hollywood, often get a leg-up over more serious works via affirming the voting body’s belief in the glory of its chosen vocation.

This ceremony was coming in hot off of the #oscarssowhite controversy. That is to say, a certain cynicism about the awards had set in and one did not expect a healthy rebuttal from the voting body that seemed part and parcel of the extant trend.

In combination with the envelope mix-up, this context made Moonlight’s victory feel like an aberration. A glitch in the matrix. The film, as Sam Adams wrote in Slate, “is the kind of story the movie industry rarely deigns to tell, told in a way that the Oscars seldom recognize… a first no matter how you come at it: the first Best Picture by a black American director, the first with a gay protagonist, the first Oscar-winning movie about black people that doesn’t foreground racism or ‘the struggle.’” You could say it was a break in reality that echoed another break in reality that had occurred months earlier when a reality TV star won the U.S. presidency.

This was the political context in which Moonlight won and there were clues this would happen in the rebukes of Donald Trump that punctuated speeches throughout the night. A meta-narrative had developed over the course of that awards season that pitted La La Land and Moonlight against one another as if they represented opposite ends of a political spectrum: the studio production about the white guy who saved jazz versus the indie film about a Black protagonist grappling with his sexuality against rigid, culturally enforced notions of masculinity.

In its most absurd form, this publicity battle morphed into the assertion that La La Land was somehow the fascist pick of the two leading Best Picture contenders – a rather embarrassing claim, in retrospect, given it came from Elon Rutberg, a creative collaborator of the man formerly known as Kanye West. Apparently he didn’t have the best radar for making that claim. But a lot has changed since then, so maybe we’ll just cut everyone involved some slack…

The point is Moonlight’s victory had this huge symbolic resonance at a time when Hollywood’s bleeding heart liberals were taken aback by the victory of a man who seemed to have secured his place in mainstream American politics via some good old fashioned xenophobia and white supremacist dog whistling – the kind of behavior many previous Best Picture nominees had decisively staked out positions against. (I mean, how many more World War II films is it going to take for people to understand the Nazis were evil?)

In retrospect, the night was an incredible opportunity for virtue signaling. You could say it was surprising that Moonlight’s victory surprised anyone. This would be the more cynical way of contextualizing the epic finale to the 2017 ceremony anyway. The more generous takeaway though – the one I am more inclined towards – is something like: who cares why Moonlight won? It flat out deserved all the recognition it got, and any occasion that truly celebrates a new height of artistic achievement is a win is a win is a win. It doesn’t hurt that Barry Jenkins has since proven himself to be one of our great living directors (see: If Beale Street Could Talk and The Underground Railroad).

So this year, in the first hundred days of the second Trump presidency, I’ll be pulling for the works I think are the best in spite of whatever non-diegetic machinations may or may not be working in their favor, because recognizing important work still matters. So please allow me to share some quick thoughts on this year’s ceremony despite my conviction that the awards are, in most any other context, silly and superfluous to the art of cinema.

First some notable omissions from the Best Picture list, pulled from a list of films that I have seen this year (although there are still many I have to catch-up on per usual):

Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World, Evil Does Not Exist, I Saw the TV Glow, Rumours, Hard Truths, Seed of the Sacred Fig, La Chimera, Between the Temples, Love Lies Bleeding, Hitman, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, Maxxxine, Megalopolis, Rebel Ridge, La Cocina, Challengers, WE, Civil War.

Some of these are just oversights on the Academy’s part: Evil Does Not Exist and I Saw the TV Glow, for example. The filmmaking in each of these is magical, not to mention the utter originality and nuance with which their directors render their thematic subjects. One is a microscopic portrayal of how even the most carefully planned human developments can promote grave imbalances in the natural world,2 the other am examination of the intersections between self-knowledge and parasociality within an aesthetic of nineties TV nostalgia.

Others make sense as omissions by virtue of exceeding the boundaries of the Academy’s aesthetic Overton Window:3 Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World and Rumours. I’ve already written at length about the former, but I think the absence of Rumours from this year's nominees is telling considering how it reflects the year in political and cultural vibe shifts. It basically sounded the death knell of a centrist, neoliberal world order months before the Harris campaign failed spectacularly in November.

The film follows the world leaders of the G-7 summit as they gather to draft a provisional statement regarding some incipient global crisis. While left at a round table at the edge of a forest, they soon find themselves abandoned, aimlessly roaming the woods after a mysterious crisis appears to have transpired. Whatever it is, the crisis is simply too large and abstract for them to respond to. Eventually they band together to get to safety and finish the important work of drafting their statement despite the absence of an audience to deliver it to.

What makes the film a riot though is how writer-director trio Guy Maddin and Evan and Galen Johnson take the polar opposite approach of the behind-the-scenes backstabbing and sociopathy that characterizes other political dramas and depict their potentates, preposterously so, with the good faith naïvete they pretend to possess in public. You can hear the Harris campaign consultants and Pod Save America bros echoed in a line spoken by the German Chancellor (played by Cate Blanchett): “We’ve been abandoned. It doesn’t make any sense!”

It is a delightful farce of the “tyranny of decorum" that has defined the Obama-era more than any other foreign or domestic policy initiatives the former president and vice president might like to hang their hats on. One moment you call your political opponents fascist threats to democracy, the next you’re sitting down with them for tea and crumpets before handing over the reins of power. It already deserves a reappraisal.

Now, of those films nominated for Best Picture, I have some brief thoughts. As you read these, please keep in mind that the point of criticism is to make subjective judgements and that I am doing A LOT OF THAT here without a ton of elaboration.4 These are just my honest, quick takes, about this year’s nominees. Apologies in advance to the Wicked fans.

Anora – I’m encouraged that a movie like Anora has attracted this much attention. Maybe it will nudge Hollywood to start making good on that suggestion Cord Jefferson made at last year’s ceremony: twenty $10 million dollar movies instead of one $200 million dollar movie. In terms of watching Anora though? Well, the first and final half hours of the film struck me as much stronger than the hunt for Ivan in between. Luckily, Madison’s performance is there to pull us all the way through. Besides, how much can one complain when a film’s final scene offers so much to mull over in a single gesture?

A Complete Unknown – If I had to defend any one of the lesser films on this list, I’d pick the Bob Dylan biopic. The screenplay, in combination with Chalamet and Norton’s performances, made for a pretty enthralling portrayal of this period of time in Dylan’s life. The film feels totally in touch with him as a character and, as a result, comes away with a theory of Dylan that actually challenges the title. At minimum it is a full-throated endorsement of an artist’s right to be free in their work. Fame and fans be damned. Maybe the filmmaking could have used an extra touch of that rebellious sensibility.

The Brutalist – I don’t think The Brutalist ever decided what it wanted to be other than a big movie. Fruits borne of that ambition: a powerful score, gorgeous cinematography, and rock solid lead performances. But when a film’s format and subject matter put it in the company of classics like Once Upon A Time in America, The Master, and There Will Be Blood, it had better have something grand to say. What exactly the whole point of The Brutalist was is still a mystery to me though. A few more passes on the script might have done the trick. (Maybe it’s a hot take, but I still prefer that other film about a visionary architect.)

Conclave – The most boring and Oscar-y nominee on this list. Ralph Fiennes can do no wrong, and his character is the most compelling part of the whole movie, but at the end of the day it's basically Knives Out in the Vatican with all the fun stripped away. At least the ending might challenge some unsuspecting audience members. I would be surprised if Fox News isn’t already running a week of stories on it.

Dune: Part Two – It’s been awhile since I saw this movie, so I’ll recycle a piece of my Letterboxd review in the spirit of Denis Villeneuve recycling his concept art from Arrival and Blade Runner 2049: “The repetitive close-ups of movie stars, doing their best to make performance art of spare dialogue, and the recycled landscape views of dull brutalist architecture, felt like sketches for a more elaborate execution of the source material. Then, enter Sandworm. Maybe I don’t have an eye for CGI, but the scene of Timothée Chalamet surfing on the back of one of these desert dwellers looks absolutely... ridiculous, no?”

Emilia Pérez – The controversy this movie has generated is even more fascinating than the film itself. I continue to be surprised by the amount of flack it’s taken. (As one Letterboxd user put it, “if aliens ever came to earth this is the first movie i’d show them to make them leave.”) But it’s a tragedy about a cartel boss who fakes her own death then, following her transition, uses the wealth she’s amassed in offshore bank accounts to make amends for her sins. Given the sheer boldness of that premise, I’m not inclined to spend too much time sweating the details. Especially when it’s so damn entertaining.

Wicked – For all the fuss about Emilia Perez, many Letterboxd users were oddly enthusiastic about this milquetoast adaptation of half a broadway musical. Watch it next to the original The Wizard of Oz (1939) and its micromanaged, color-corrected aesthetic could take your breath away. For all the fuss about there being real flowers in those fields and the performers really singing the songs, who could tell after the hundreds of technicians listed in the closing credits managed to flatten all the life out of every frame. Seriously. Just watch Judy Garland sing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” then tell me with a straight face about how you can’t wait for Part Two.

The Substance – I would highly recommend NOT reading the film as a statement piece of any kind. For the first ten minutes I suspected as much. The bluntness of the images had me scoffing, and I was prepared to settle in for two hours of hate watching. Then Demi Moore birthed Margaret Qualley out of her back and I was hooked: the body horror multiplies exponentially from there. Call it hyper-expressionism. That being said, if you aren’t dying laughing by the end, it probably isn’t for you. Respect to Coralie Fargeat for going there.

I'm Still Here – This is the film on the list that speaks most directly to the rise of authoritarianism all around the globe. Late in the story, a reporter asks Eunice Paiva (Fernanda Torres) whether the government has more urgent issues than making amends for crimes of the past? She responds, “No. I think it's absolutely necessary to compensate the families and do the most important thing, clarify and judge all crimes committed during the dictatorship. Otherwise, they will continue to be committed with impunity.” As Salles demonstrates by example, so too should the cinema continue to concern itself with crimes of the past. Some histories need to be captured more than once too. Which finally brings me to…

Nickel Boys – Far and away the film of the year. I was so happy to see it nominated, but bummed to see Ross snubbed for Best Director. A tremendous oversight – what does the Academy think a director does exactly? My only theory is that it was too groundbreaking for them to take in on a single viewing. I hesitate to speak so grandly about a movie I myself have only seen once, but I predict it will mark a paradigm shift in the way independent narrative films are shot and conceived. There are other reasons why Nickel Boys should win Best Picture though and I would like to detail them below.

First, it should be noted that the cinematic style of Nickel Boys is not without precedent. Jonathan Demme's films, for example, are packed with fourth wall breaks. But note how, in Silence of the Lambs or Something Wild, his characters rarely (if ever) break eye contact with the camera once the angle is established. This rule does a bit of work in hiding the effect and maintaining the immersive quality of the narrative. Nickel Boys, on the other hand, embraces a full spectrum of performance within its wall breaks. Ross does not do any work to hide them.

For many, I imagine this choice will have the somewhat disorienting effect of submerging one in Turner's and Elwood's subjectivities while at the same time drawing attention to the filmmaking. But I found the more I adjusted to it, the more this doubling effect dissipated and lended attention to the film’s powerful narrative elements. In this way, the movie forces a fundamental question about cinematic style into the conversation: why is it so unusual to film from a first person or close-third person point of view? What stories have not been told as a result of the exclusion of this perspective?

Ross has said the camera angle was a natural decision for him, given his background as a photographer, but for a narrative film it feels radical. This is why Nickel Boys is the artistic achievement of the year. It makes that basic act of looking feel new again.

If there is one movie more people should see on the Academy’s Best Picture list, this is the one. So will Nickel Boys get all the recognition it deserves like Moonlight did back in 2017? It’s hard to say. I’m not in touch with all the extra-cinematic machinations surrounding this year’s ceremony. At its worst the Oscars are simply a theater kid’s Superbowl: another superfluous celebration of our country’s statistical outliers in terms of net worth, keyword searches, genetic endowment, and fossil fuel emissions. But if merit alone is enough to win then I think Nickel Boys has a great shot. And so long as the Academy ascribes to the belief that there is a consensus way of recognizing such achievements, they might as well get it right again this year.

Take the 2012 ceremony in which voters championed the least rewatched (I would wager) Best Picture winner of the 21st century, The Artist (2011), over heavy hitters like Moneyball, and Midnight in Paris. Its win over Terrance Malick’s The Tree of Life though was totally absurd.

Try pairing with Kohei Saito’s book Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto.

Despite the conviction my language may betray, I always love a good rebuttal, so please don’t be afraid to comment or DM me.